By: Winta Assefa

I arrived at the Addis Ababa International Airport on a cold Sunday morning. The air smelled different from the start.

For a moment, it felt like the perfectly messy utopia I'd imagined for some time. But there were signs this might not be a better place, even at the airport. In the luggage reclaim area, a young man was on the floor, with his head in his hands and a group of people trying to comfort him. He may have been forced to return, and there's a stigma around people who leave their hometown to make more money only to be deported empty-handed.

And I knew I was privileged to be welcomed here even when I was empty-handed. That's not often the case.

Since Dad had already prepared our paperwork a couple of months back, I managed to get into a school on my first few days. Part of me went, ‘oh, so it was that easy? I didn't have to write any of those newspaper articles or wait for middlemen to finish my paperwork. I could've just come here.’

I sat in a classroom for the first time in years and immediately made friends with a fellow Saudi-born Yemeni girl. She reminded me of the people I had just left. But a few things were new to me: I never had boys in my classroom or saw women drive their kids to school. There was nothing difficult to get used to, though. I picked up the A-Level exam studies I had paused and borrowed a children's book from my school library to learn the Ge'ez alphabets*.

Upon my arrival, I neither knew how to speak nor read in Amharic, the National language. But after a couple of months of memorizing that kids' book and asking the librarians questions, I started practicing my reading with the billboard signs we passed on our way to school. It helped that the Ge'ez alphabet is the most logical one I know—it neither had English's bizarre rules nor Arabic's complex alphabet-attachment requirements.

After graduating high school, I got into the Ethiopian Institute for Architecture, Building Construction and City Development (EiABC), the biggest architecture school in East Africa. Through spending time there and on-site visits, I really began to understand why some people would cross the sea to come to the place I fled from.

There were times I met other returnees from the Middle East who worked in-campus or at a site we visited. I was often impressed by how well they spoke Arabic, given how long they spent in an Arab country. I believe one can only pick up a language that quickly if a lot depends on their learning speed.

It's probably why it took me such a short time to communicate in Amharic as well. Although English is said to be the 'official language' on campus, many teachers taught in Amharic so that students who struggled with the English language could understand their subject better.

And since I was the only one who didn't understand Amharic in a class of over a hundred people, I didn't want to create an inconvenience.

So, I learned the language like a child would: by imitating those around me and getting corrected along the way. I think the fastest way to learn a language is also the least comfortable and most humbling.

Another thing happened after a few years on campus too. I experienced a couple of miraculous events that encouraged me to delve deeper into the Christian faith. I made friends who helped me on this journey, and soon enough, my perspective on everything had changed.

All the anger I harbored for the people who ran my birth country began to dissolve. I felt like my 'identity issue' was resolved as well: I no longer needed to belong anywhere on this planet. My God is Love, and He invited me to be His daughter in a Kingdom that isn't run the way earthly kingdoms are.

This may just sound like a convenient idea to hold for somebody who never belonged in any country—and I must admit it's difficult to prove that's not the case. But I don't feel the need to prove anything to anyone anymore, and I'd never been this free.

Still, while I'm on this earth, there are several things I'm yet to figure out as an adult. I'm just glad my whole identity does not depend on them.

But it doesn't help that my friends and I graduated in one of the worst eras of the construction industry. We held our graduation ceremony on a shade-less football field to lower the risk of spreading COVID-19. None of the optimistic speeches there could shield us from the reality that awaited us, though.

Months later, I found myself at another standstill: how could I be financially self-sufficient in a time and place like this? I learned that lately, the average salary set for junior architects can barely cover their transportation costs.

Often, senior architects rely on junior architects to build entire designs on modern software. Some people speculate that these low salaries had been imposed by senior architects to discourage younger, more technologically-versed architects from staying in the field—thereby cutting competition. This theory sounds a little extreme to me.

But after just a year, I already know many people who switched to other professions. Several of them had been working on multimillion-birr projects on wages they couldn't survive on. We can't legally open our architectural firms without first getting years of 'experience' at an established firm, either. So, it's an iffy time to be a new architect here.

So lately, more and more people have been suggesting that I go back to Saudi Arabia.

'You already know the language and culture. It'll be easier for you to land a job', I was often told.

Their idea sounds reasonable: I suppose I could sign up for a five-year contract there, make some money and return. But I just couldn't take that idea seriously. Now isn't a good time to be an Ethiopian there.

So, I'd been trying to do valuable work online instead. And I have to admit I'm having a hard time making this transition.

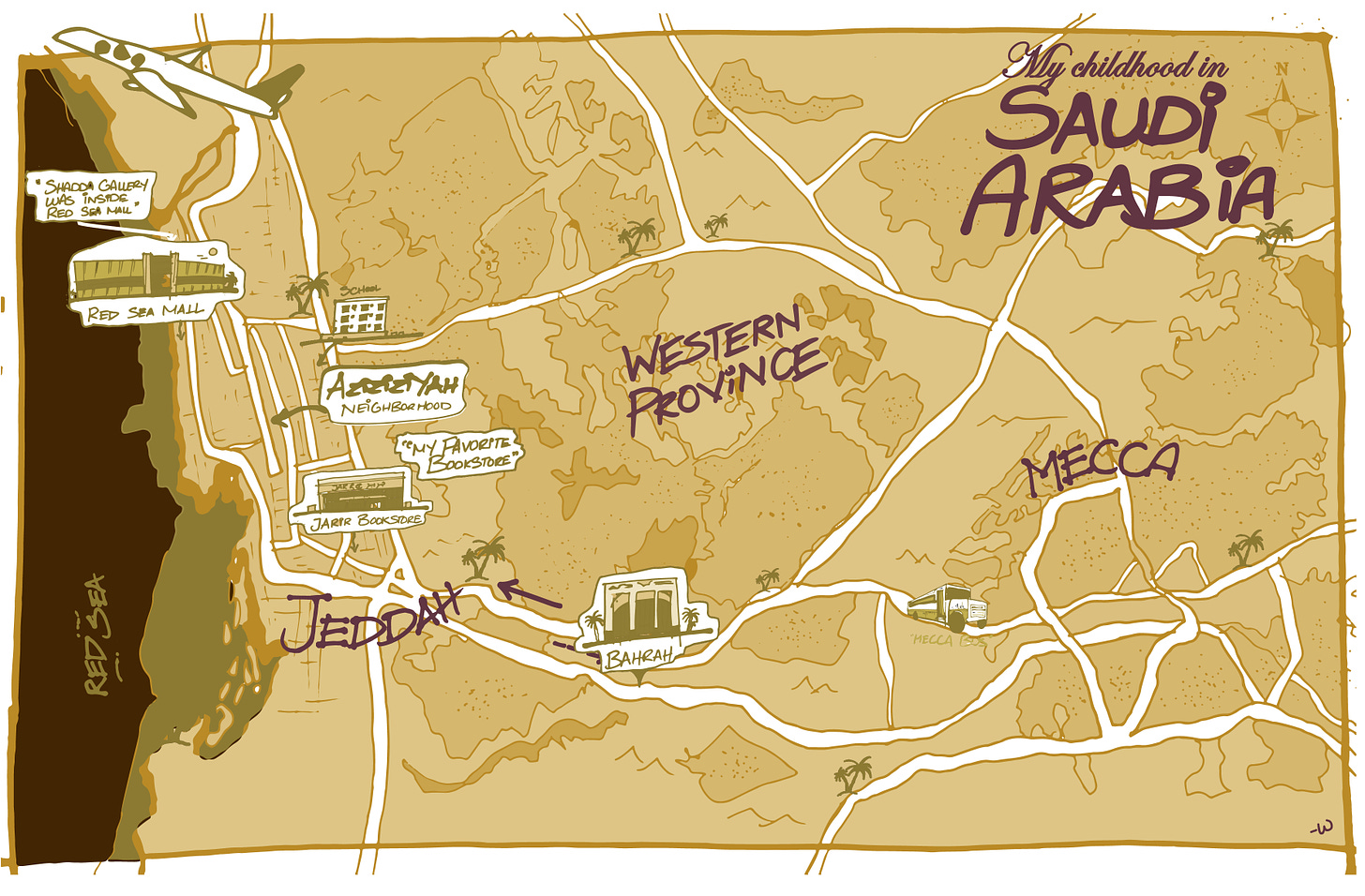

And when things get hard, I keep catching myself going back and wondering what would've become of the different projects I started if I had carried on with them. What if I went from playing those sand art shows in Shadda Gallery to performing in bigger venues until I was a well-known visual artist? Would the money and status that comes with that level of recognition have shielded me from everything else that other foreigners had been going through? What if my Arabs Got Talent audition went well, and I ended up on the show and on millions of Arabs' televisions? I probably wouldn't have wound up in Ethiopia wondering how I could make a living working online.

But then again, I probably wouldn't have found the faith that transformed and healed me either. So I wouldn't change anything about the past few years.

Meanwhile, I see the Saudi Government authorizing massive urban projects that look like their designers had little to no limitations (the free satellites here broadcast the same Arab-language shows we grew up with, so we still have many updates about Saudi Arabia).

The Middle East, in general, feels like it had become a playground for displaying egos: who's going to build the next tallest' vanity building' in the world?

I don't think Ethiopians are above this mindset, though. Many of the wealthier Ethiopians who return from Dubai-which feels like a parody of a city to me-come here and hire local firms to duplicate a building they'd seen there.

And so, in the past few decades, Addis Ababa had become filled with bad replicas of uninspired buildings.

That’s not what I want to do. I don't want to participate in massive masterplans and expensive buildings meant to boost the country's standing. But nothing I can brag about here could last very long. So, instead of accumulating wealth, I want to share (just like Christ does).

And I realized that I already have more than many.

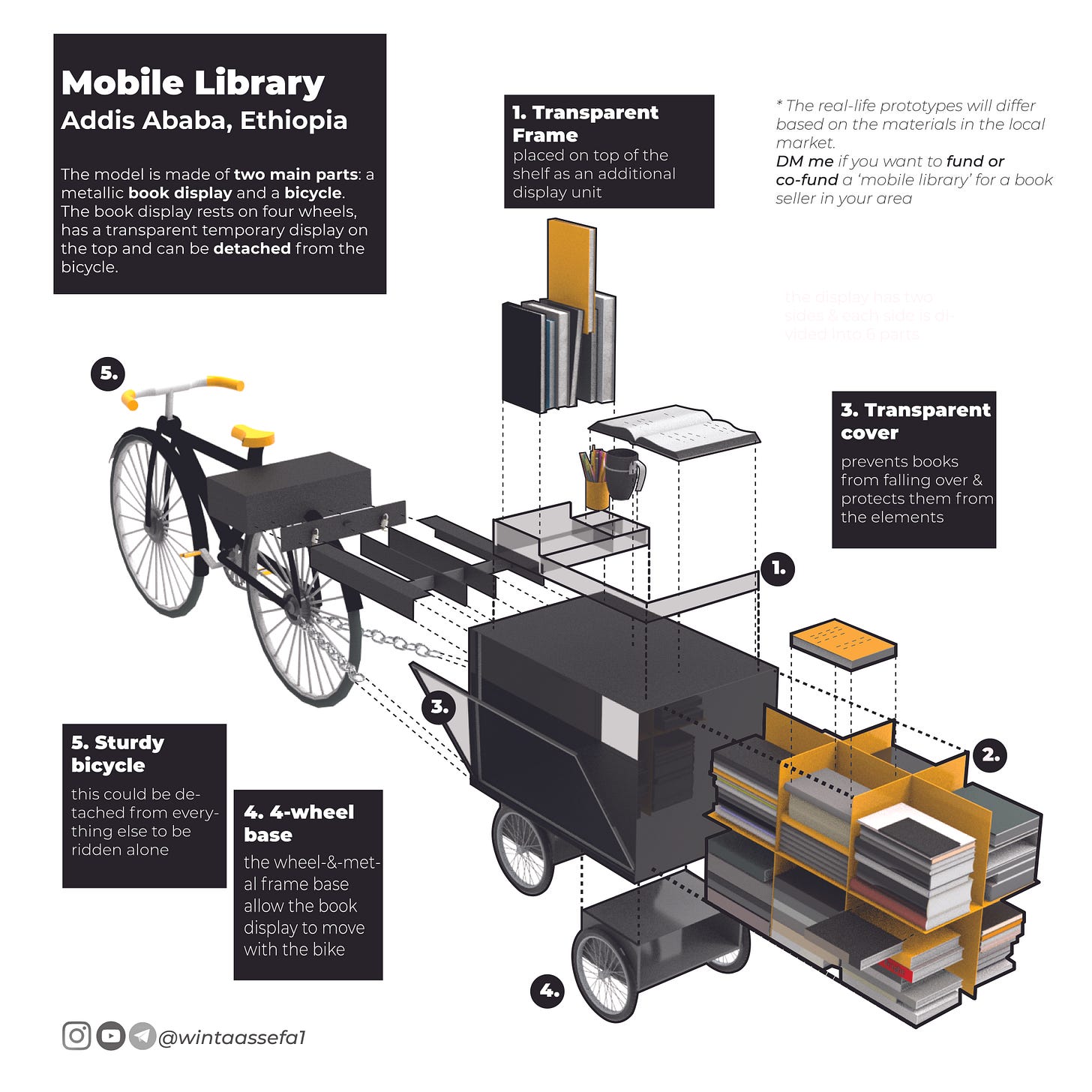

So far, I won the opportunity to design a Berkeley-funded mobile library prototype for the young men who carry and sell books on the streets here. Unfortunately, neither of my collaborations with local workshops had worked out. The first one scammed us using cheap, ineffective materials, and the second collaborators couldn't execute a safe and fully-functioning design.

Still, I was able to find several individuals who were willing to lend their resources and expertise to the project. Their generosity inspired me to someday start a network for scientists and creatives who could pool ideas to develop solutions for underserved people here.

Working on projects like this may be how we could begin to take people out of a position where they believe embarking on dangerous journeys to the Middle East is the best way out.

But once in a while, I have more human sentiments. I remember some things about my time in Saudi Arabia, all the time I wasted out of school, and I feel petty. In moments like those, I want to be so big 'they'll' regret making me leave.

I start to feel like a bitter former lover—and that's when I allow myself to miss my birthplace.

I still get close to tearing up when I hear Mohammed Abdu's singing. I get emotional when I see Al-Baik's Fried Chicken packaging somewhere-even though I'd been a vegetarian for five years now and few things make me feel as nostalgic as hearing somebody speak in a Saudi dialect.

And the more time passes, the more I'm aware that after all of these mass deportations, no other generation may experience the rich potpourri of cultures that we had growing up.

So, I'm grateful for the richness and rarity of that experience.

But now, I look forward to something else.

*Ge'ez: one of the most ancient languages in the world, its alphabets are now used in several Ethiopian languages

It's Win-tuh, kind of like how British folks say winter. Architect, storyteller, & cat-mom from Ethiopia. Read more of my stories here.