Outcast

In the second half of 2004, dad sent my sister and me to an international school for the first time.

Before that, I was taught how to write in English in a Sri Lankan woman's home-based school. Dad had met her at her furniture sale when we were still toddlers. She let him know that she had a Master’s degree in English and was about to start her own little school.

By 2001, she made that happen.

On my first day of school, Dad and I received a warm welcome at her palm-tree-surrounded new place. She was a self-assured, round-faced woman who had to bow to greet me face-to-face. I didn’t know what she talked to my dad about and what she said after he left us alone. I knew no English back then, but she didn’t seem to be concerned by that, and I was trying to conceal my excitement of finally being in a school.

Later, I learned that the boxes in front of the door contained colorful lego pieces which we could play with on her carpeted floor. I’d started wearing longer outfits to avoid getting rugburns there. On certain occasions, she’d take a break from our usual schedule to teach us how to bake cookies and make homemade play-dough. With all the illustrated storybooks, the Pinnocio cartoons on all our report cards, and smiling characters and toys on the walls surrounding us, it felt like we were in a tiny rendition of the Disney World in the middle of the Saudi Arabian desert.

But by the mid-2000s, she started having a hard time teaching us math. She hired her son to do it, but he clearly didn't enjoy the task. And I didn't have a knack for mathematics even then.

So it was time to move elsewhere, and Dad settled on Al-Hejaz International School. Unlike being homeschooled, that place was not a single woman's brainchild. It was a well-established machine that rolled out scores of graduates every year. Because it's a licensed entity, the school could ship in teachers from countries like the Philippines and have them sign eight-year contracts to work exclusively for them. I went from a home with a dozen students to what felt like a cold, little simulation town. There was no warmth there, nobody watching your back.

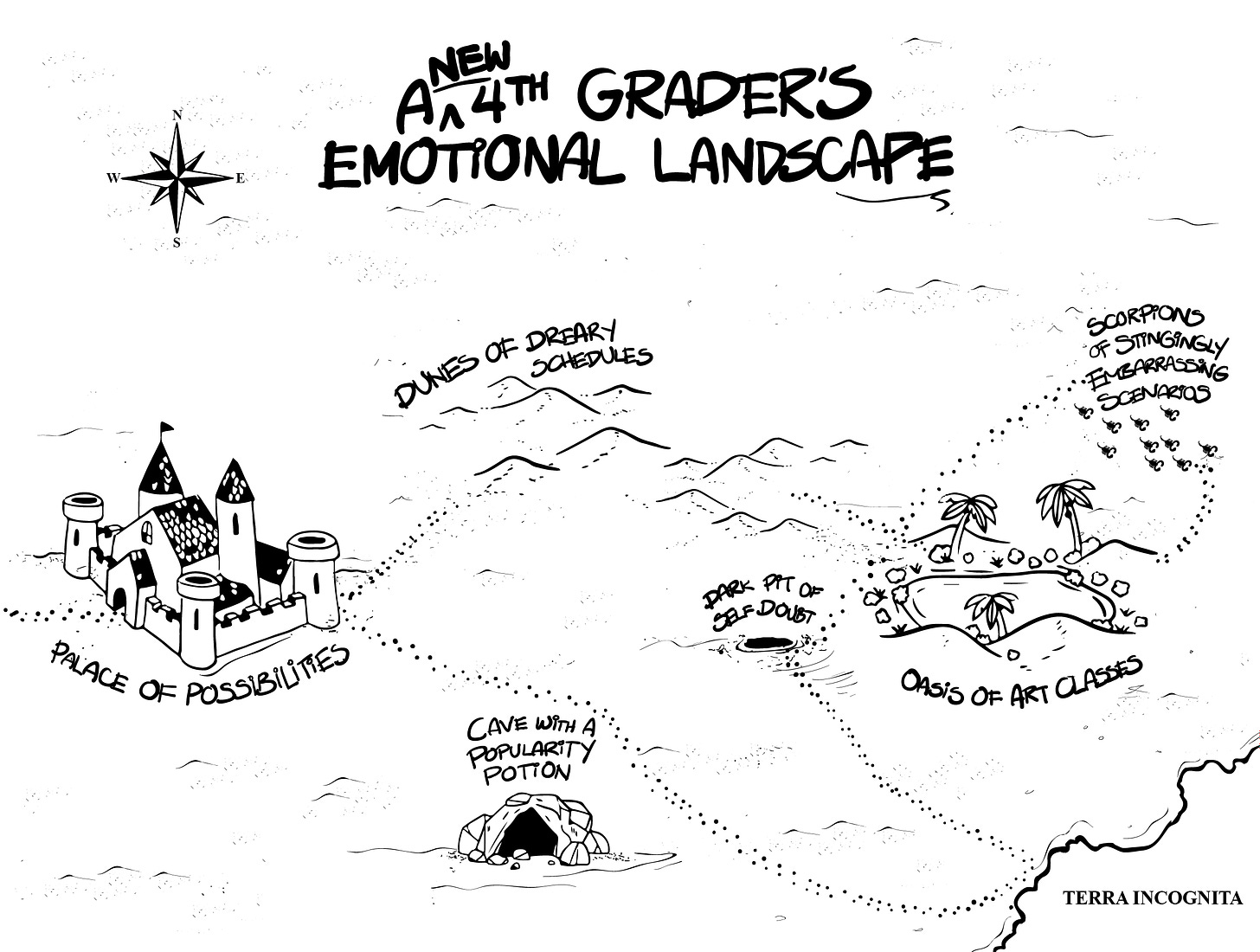

The boys and girls were separated into different classrooms. I don't remember interacting with a single fourth-grade boy. It was big enough for the students to have formed social hierarchies, and since most of my classmates had been there from the beginning, it felt like I'd walked into the second episode of a show's third season. I had no idea how to catch up.

How do we decide who should be the most popular kid at that age anyway? Does one child start treating the next kid better than the others, encouraging everyone else to follow suit?

I always wanted to be liked by them, though—no matter how arbitrary their reason for it.

From the beginning, I kept wondering where I had gone wrong. Maybe if I had spoken up louder on my first few days, they would've thought I was confident and not someone to be messed with. Perhaps my parents’ Christian faith and the fact that I didn’t have to take Islamic Studies classes with them was what primarily bothered them: I was a kaffir*, the only infidel in class—in a country where more than 90% of the population were classified as Muslims.

Or maybe everybody could see right through me; they may have had an idea of what I thought of myself. I hated being the kinkiest-haired, darkest-skinned kid in my class, and I kept comparing myself to girls with fairer complexions and softer curls.

But something that made me believe my physical appearance wasn’t an issue was my sister a couple of grades down. She was one of the coolest kids in her class, so I thought I must be missing it somewhere.

Now an Egyptian girl I'll call Mariam* was the most popular kid in the grade. She was even acknowledged by the fifth graders next door. Mariam had a square-shaped face and curly dark-blond hair that reached her butt. Nobody wanted to get on her bad side. The Southeast Asian girls had their own sub-group, headed by Aisha*. Neither group seemed to hate each other, but they mostly stayed out of each other's way.

Mariam was intelligent and influential enough to get the class on her team whenever she needed to. This became clear to me from the beginning.

When I first joined the school, dad hadn't bought all of my school books yet. There was one math practice book that I especially needed. When he finally bought it, he wrote my name on the front page and passed it along to the school administration to give it to me. I think I was in class on the last day before our winter break, so I wasn't available to get the book myself. Later in the day, I was handed the book.

Incidentally, Mariam had lost her math practice book around the same time. So, when she saw me with my new book, she got an idea.

'Can I see the book?'

'Okay.'

I gave it to her.

She calmly said that she had lost her workbook and that the one I had could be it. When I asked her how my name was written on the front then, she didn't budge.

'I'd written my name with a pencil. You could've easily rubbed it off and replaced it with your own.'

Mariam wasn't violent: she didn't need to be. She made her case with confidence and ease. I imagined a thought going through everybody's head: Winta, the thief!

I felt sick and stuck. I wanted to scream, but I didn’t want to appear desperate. I wanted to drag in somebody from the school administration, but I didn’t want to be too dramatic. My classroom’s pale, blank walls echoed back our words as if to mock me.

It had taken just a few minutes for her narrative to be set in stone. It was her word against mine, apparently—and her word carried much more weight than mine.

When the verdict went out, I felt weak and dumb. The jury was biased, and the judge was the plaintiff herself.

I don't know how I let her take the workbook from me, though. I imagined snatching it away from her, surrounded by dozens of girls who didn't believe me. She was giving me too much credit with her claim that I thoroughly rubbed off all of her work and made the book look brand new. But we were little fourth-graders, and 'truth' is often decided by the most powerful one anyway—in that classroom and beyond.

I got my book back after the winter break. But I could only do that by letting the administration know what happened (little snitch, huh?)

One of our teachers took the book from Mariam to give it to me but not before giving her a lecture. The girl sat there like a dignified person making peace with the consequences of an honest mistake.

Those other girls must have hated me even more at that moment.

At least, that’s what I thought they thought. That incident hadn’t changed much with our social order, though. Mariam was still bright and popular, and I was struggling and odd.

I couldn’t give my classmates full credit for my experience there, though.

Our swimming teacher seemed to find my presence particularly agitating. Her eyes were the blue of the heavily chlorinated pool we swam in, and I don't recall her ever smiling. I think I'd heard her speak in an Egyptian dialect with a few students: she had formed some sort of camaraderie with kids like Mariam, girls who made her job easier. But I only got her weary looks—oh, how badly I wanted to make her proud!

But I was so bad at swimming, she must have been convinced I was messing with her. After months of trying to teach me, she seemed to have given up. Most of the other girls had been swimming since they first joined the school, while others seemed to pick up swimming basics quickly.

I found that so infuriating! The water seemed to join everything and everyone that was conspiring against me that year. Every time I tried to float, I was drawn to the bottom like something being pulled by a supernatural force.

I would see Mariam alternately swim on her back and on her belly like a mermaid, wielding the water as she wished. Encouraged by the apparent ease of her swimming, I'd try something she did only to end up splashing so much, froth formed around me. Instinctively, the other kids swam away.

In the fourth grade, being good or bad at anything seemed to contribute to one's popularity scoreboard.

Coming last in a race in a full playground is something forgivable.

But flailing one’s arms like a toddler throwing a public tantrum could turn one into an embarrassing person to be seen with. Nine years old seems to be the perfect age for trying something out without judgment—but people are brutal.

The reason I was persistent is because I loved swimming pools. I liked those blue bodies of water since I saw them in the compound where my Sri Lankan teacher's house was located (we weren't allowed to use those, though). I just wished those pool bottoms didn’t love me back so much.

Though I often came home hurt, frustrated or confused, I didn’t want to tell my parents about most of the things that happened because I thought this was my chance to prove myself in a ‘proper’ school. I thought I had to grow up and handle things myself.

Years later, I found a message on Facebook addressed by a familiar name. Aisha. She left a long letter apologizing for everything she and her friends made me go through at Al-Hejaz.

I was fourteen years old when I read her message.

But I was reminded of Hasan Minhaj's words in his comedy special: 'When you see someone from your past, all of a sudden, you're that age again.'

Though I had changed schools in the city and I wasn’t the least popular kid in class anymore, that apology had meant something to me. I thanked her for reaching out to me and saying everything she did. I had a hard time talking casually to her, even as a teenager.

But she was never the real enemy. Neither was Mariam or the school instructor.

It's Win-tuh, kind of like how British folks say winter. Architect, storyteller, & cat-mom from Ethiopia. Read more of my stories here.