I was sitting on the warm-up bike at the Reikes center training facility watching ESPN. It was the spring of 2002, and I was near the end of my rehab from shoulder surgery earlier that winter. The Reikes Center was a one-of-a-kind non-profit facility that served as part training, part mentorship, and as an incubator for the musical arts.

I was in my Junior year at Stanford, and although I was the starting running back, I missed winter training and would miss most of spring football practice. Our former head coach, Tyrone Willingham, accepted the job at Notre Dame in December of 2001, so a new coaching staff would evaluate us during the spring. The new staff, led by head coach Buddy Teevens, were still getting to know all of us on and off the field.

Stanford was a unique place. Building great athletes wasn’t more important than building great men, so the standard for on-field performance was on par with classroom expectations. That year, we just came off one of our best seasons where we finished ranked #16 nationally and were all excited about the potential for our upcoming season.

As I was finishing my warm-up, a breaking news alert scrolled across the bottom of the ESPN ticker. Curtis Williams had passed away. He was the former football player from the University of Washington who was left paralyzed after a collision during a game against our Stanford team in 2000.

The football community is close-knit. We all understand that the game is inherently dangerous, and tragedies like this reminded us all how vulnerable we indeed were. For many of us, the memory of watching someone get carted off the field without moving their extremities was an unforgettable first. For me, it was the silence that I remembered. In most instances, you didn't even need to watch the play but simply listen to the crowd's roar to know if the home team had a positive result. On that particular play, what started as cheers quickly turned to a deafening silence. At that moment, I knew something was really wrong.

Some of my closest friends on the team were from Seattle and knew many of Curtis' teammates. We didn't learn about the severity of Curtis' injury until we got to the locker room after the game.

I remember the conversations we typically had after a game. We talked about how the game we loved forced you to have a superhuman mentality and unshakable confidence in your abilities. But on that day, we talked about feeling mortal, unsure, and hesitant.

10 minutes passed; as I watched the news scroll across the ticker again, my thoughts went to Curtis’ family. I thought about his mother, brother, 7-year-old daughter, and my heart ached thinking about the loss they felt. It was traumatizing enough to see someone they love paralyzed. But up to that point, he still had his life and, in turn, hope. The finality of his passing removed all of that.

Curtis' death forced me to relive that day, that game, and those circumstances that led to his paralysis in great detail. As football players, we all identified with him. Even though we never talked about it, the fear of something like this happening was like a dark cloud looming over the stadium. Even though I understood that this incident was an anomaly, the danger still existed every time I stepped out on that field.

I couldn't help but think about the fear he felt as he laid there motionless. I could feel my heart racing at the thought of him opening his eyes but unable to control his body. For me, this game had been such a big part of my life since I was about 12 years old. When something like this happens, you can't help but ask yourself whether the benefits outweigh the risks.

Football was our ticket. This sport gave us the ability to follow our dream doing something we were passionate about and excelled at. It gave us the ability to pursue higher education and the ever-looming allure of the riches of making it to the "League," the term we used for playing pro in the NFL.

For me, it was an opportunity.

Growing up as a young boy in Trinidad, I loved sports. I played everything from cricket, soccer, basketball and track and field. "American Football," as we called it, wasn't something I knew much about or even understood. I remember watching part of a game with my uncle Ian when I was about six or seven years old and asking him, "Why do they keep running into each other? I would just use my speed to run around everyone."

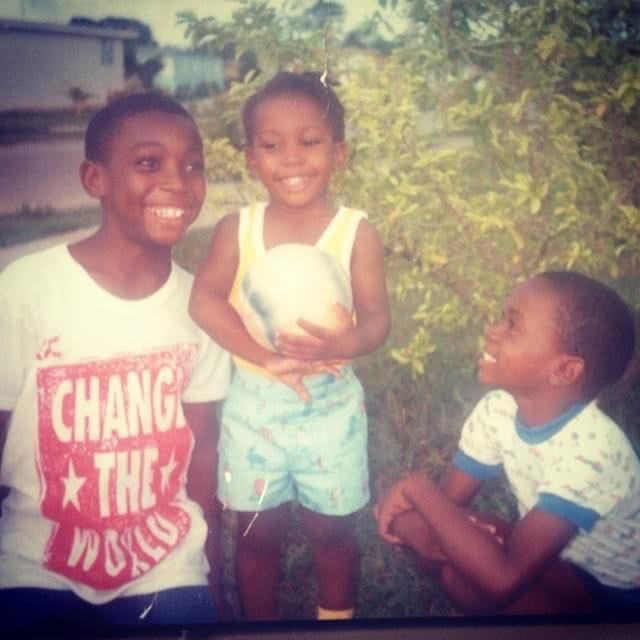

When I was nine, my mom took my two younger brothers and me and moved to Toronto. Our grandfather, my mother's dad, and much of the Douglas side of the family lived in Toronto. My mom spent nearly two years away from us making arrangements for us to move to Canada. It was a move that would change the entire trajectory of our family and allow us opportunities that we never even dreamed of.

When we arrived in Toronto, we adapted well to the culture. The fact that we had family there was comforting. Still, the number of families from other islands in the Caribbean and countries in Africa was even more surprising to me. Life was different there, beginning with the blistering cold winter weather. Still, the possibilities were endless, and so were the options when it came to sports. My brothers and I jumped in headfirst and wanted to try everything we could.

We lived in a high-rise apartment on the corner of Weston Road and Sheppard, government housing. Still, all we saw was a wonderful tight-knit community and other families who were experiencing Canada for the first time. There were kids our age everywhere, and we quickly made friends because of our shared love of basketball and playing tag in the fields outside each building that became our make-shift playground.

We tried new sports, like baseball, hockey, and volleyball. It wasn't until I was in 6th grade that my middle brother Kern wanted to play football in a league that he heard about through some of his friends. The only way he could play is if I agreed to sign up with him to take the bus together to practice. I can honestly say that I didn't really know what I was signing up for. I had only watched parts of games since commenting to my uncle, and I still didn't understand the rules or positions.

It wasn't until I got to high school, where I got a chance to play running back, that I really started enjoying football.

After my first high school season, I dedicated myself to training to be the best. In addition to the various in-season practices, I went to lift at Gold's gym three days a week. I spent another three days working on my speed training on the track at York University, a local institution not far from where we lived.

As a sophomore in High School, I helped lead our team to a provincial championship and was named MVP. I concluded my high school career by winning the Harry Jerome Award as the top student-athlete in the country and received a full athletic scholarship to play football at Stanford University. This was an honor that made my mother the proudest, as the sacrifices she made to give her children a chance at a better life were paying dividends.

My mom worked as an emergency room nurse at Branson Hospital, and of all the lessons she taught us, compassion and empathy were at the top of the list. She raised three young boys as a single mom in a new country, and I don't remember ever hearing her complain about our situation. I don't even think we ever saw ourselves as anything other than blessed and fortunate to be surrounded by love.

This was ingrained in us, and as I sat on that bike, somewhat frozen, my mind flashed back to that game. I could feel an ache in my shoulder; it was like I was back in that moment. Almost 20 minutes passed, and my trainer was ushering me out to the turf field on the other side of the Reike complex.

Instead of heading to the area, I went into the locker room and grabbed my phone. I had numerous missed calls and messages waiting for me. I didn't finish training that day; I couldn't. The news of Curtis' death weighed heavily on me.

I was the one he ran into on the field that day. I was the one he tried to tackle when he got paralyzed.

Damn, I could only imagine the guilt.